“To fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence; supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting.”

— Sun Tzu, The Art of War

This oft-cited maxim not only encapsulates centuries of Chinese strategic thinking but also prefigures a modern concept increasingly relevant in global security discourse: hybrid threats. Coined by Frank G. Hoffman in 2005, the term refers to a form of warfare blending conventional and unconventional tactics, state and non-state actors, and overt and covert strategies—often remaining below the threshold of open conflict.

As Europe grapples with this evolving threat landscape, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) emerges as a particularly complex actor. This article explores how “hybrid threats with Chinese characteristics” manifest in the EU context and how China strategically exploits political and economic levers to erode cohesion and assert influence.

1. Understanding Hybrid Threats

The EU’s own understanding of hybrid threats remains varied across institutions. The European External Action Service (EEAS), in its 2015 Food-for-Thought Paper, characterizes them as centrally planned combinations of military and non-military means—including cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, and economic coercion. The European Commission frames hybrid threats as coordinated attempts by state or non-state actors to exploit EU vulnerabilities while staying below the threshold of formal warfare.

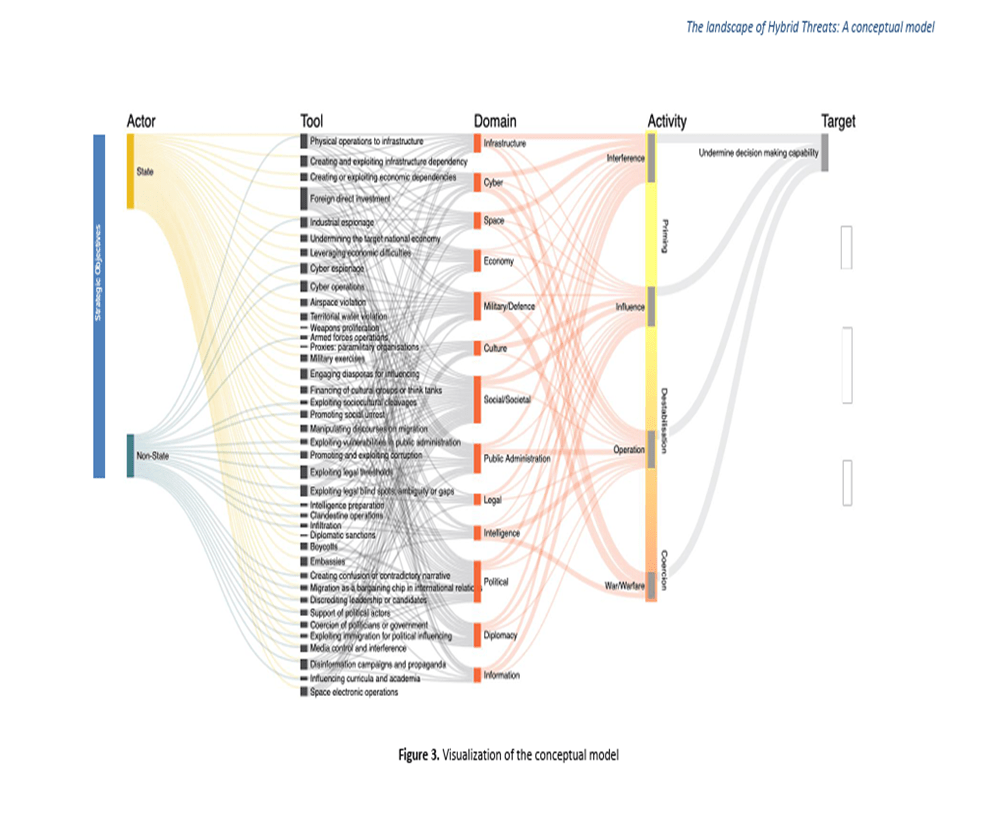

The Helsinki-based Hybrid CoE adds another layer: it highlights how digital technologies and societal openness expand the reach and effectiveness of hybrid tactics. Its analytical framework dissects hybrid threats through four lenses—actor, tools, domains, and phases—to provide a structured approach to identifying and countering them.

2. China as a Hybrid Threat Actor

Chinese Strategic Culture

Chinese strategic culture is shaped by three intertwined traditions:

- Strategic Deception and Non-Military Warfare – Rooted in Sun Tzu and reinforced by the CCP’s adaptation of Confucianism and Communist ideology, Chinese strategy emphasizes long-term planning, psychological pressure, and victory through influence rather than confrontation.

- Exceptionalism – China’s “with Chinese characteristics” approach signals a deliberate departure from Western norms. It claims uniqueness in its policies, projecting its model as a civilizational alternative to liberal democracy.

- Historical Revanchism – The narrative of the “Century of Humiliation” frames China’s rise as a rightful return to global prominence after Western and Japanese subjugation.

Under Xi Jinping, this culture has taken a more assertive turn. Xi’s rejection of Deng Xiaoping’s cautious “hide your strength” doctrine marks a strategic shift toward proactive global leadership. His vision of a “historical window of opportunity” underpins efforts to reshape global governance in China’s image by 2049.

China’s Three Wars Concept

Codified in 2003, China’s “Three Wars” doctrine—public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare (lawfare)—guides the CCP’s hybrid tactics:

- Public Opinion Warfare aims to shape narratives, mobilize domestic morale, and erode international support for opponents.

- Psychological Warfare targets decision-makers with disinformation, coercion, and manipulation to weaken their resolve.

- Lawfare uses or reshapes legal norms—domestic and international—to legitimize Chinese actions or paralyze opponents.

These tactics are not isolated but synergistic. They form part of a broader doctrine known as Comprehensive National Power (综合国力), which encompasses military, economic, diplomatic, and technological capacities in pursuit of strategic objectives. Key tools include the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the “Made in China 2025” industrial strategy, and China’s global initiatives (e.g., the Global Security Initiative and Global Civilization Initiative), all reinforcing its vision of a “Community with a Shared Future for Mankind.”

3. Hybrid Threats with Chinese Characters against the EU

The PRC has developed a sophisticated playbook to exert influence within the European Union by exploiting its institutional architecture, political divisions, and economic dependencies. These hybrid threats are not isolated incidents but part of a long-term strategy aimed at reshaping Europe’s political and economic landscape to align more closely with Beijing’s interests. Beijing’s hybrid activities in Europe aim at three interrelated goals by exploiting the institutional and systemic vulnerabilties of the European Union to achieve its foreign policy goals using a multitude of tools:

- Undermining EU Political Cohesion – by exploiting the EU’s unanimity requirements, especially in foreign and security policy – Beijing can paralyze or dilute European decision – maing on sensitive topics, particularly related to China itself.

- Challenging the EU’s Global Credibility – by weakening its voice in multilateral forums.

- Expanding Chinese Leverage – by deepening asymmetric economic dependencies through investment and trade, China creates incentives – and implicit threats – that shape national policy in its favour.

Hereby the PRC is making full use of its „comprehensive national power“.

Infrastructure and Economic Dependence as Strategic Leverage

China’s economic statecraft in Europe, particularly since the 2008 financial crisis, has relied heavily on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in critical infrastructure, often under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While initial enthusiasm saw 18 EU member states sign MoUs with Beijing, recent years have seen some disengagement, such as Italy’s withdrawal from the BRI and the Baltic States’ exit from the 16+1 mechanism.

Yet the structural vulnerabilities remain. Chinese FDI continues to focus on high-value sectors like logistics, telecommunications, energy, and advanced manufacturing. These investments are not purely commercial—they serve geoeconomic purposes that enable hybrid influence.

Ports as Geoeconomic Chokepoints

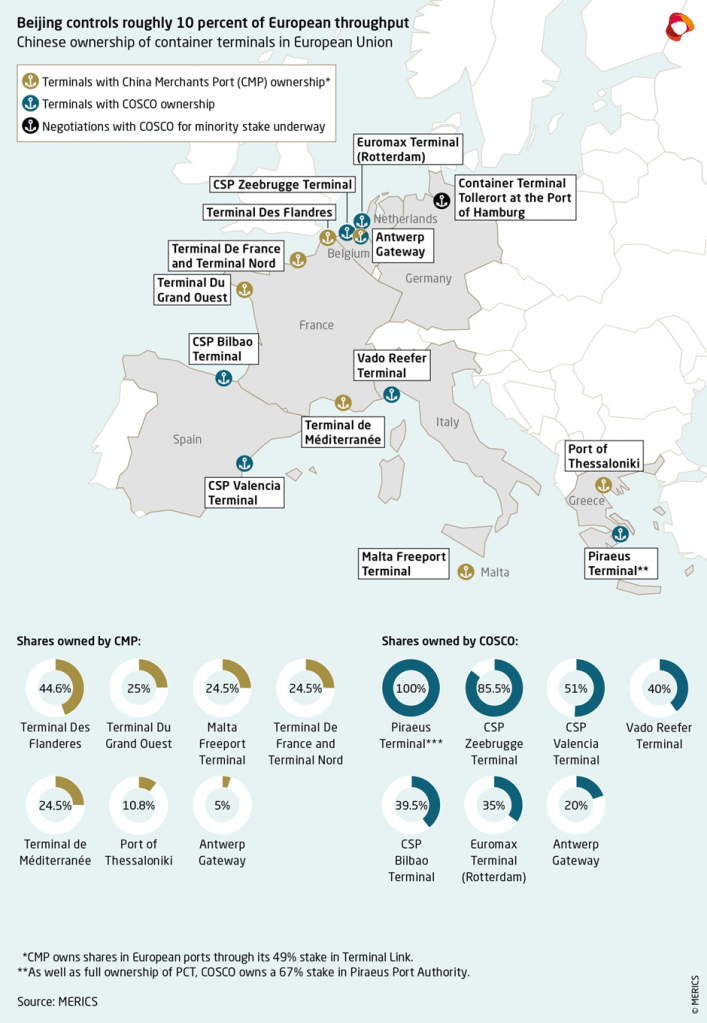

One of the clearest illustrations of Chinese hybrid influence is the acquisition of European port infrastructure:

- In Greece, the COSCO Group, a Chinese state-owned enterprise, acquired a 35-year lease on two piers at the Port of Piraeus in 2009, later increasing its stake to become the majority shareholder of the Piraeus Port Authority. This acquisition occurred during Greece’s economic crisis, when Beijing strategically offered investment where Western partners hesitated.

- In Belgium, COSCO holds a 24% stake in the Zeebrugge port, a major node in Europe’s shipping network.

- Spain, France, Italy, and the Netherlands all host ports with terminal operations partially or fully controlled by Chinese companies. By 2020, China controlled or had stakes in terminals handling over 10% of Europe’s total shipping throughput.

These acquisitions create leverage in multiple ways:

- Policy Influence: Countries that host Chinese-controlled assets may feel pressure to align with Beijing’s diplomatic preferences, or at least refrain from criticism.

- Narrative Control: Investments are often accompanied by public relations campaigns or media partnerships that frame China as a reliable and indispensable partner.

- Legal Constraints: Investment protection treaties and ownership rights make countermeasures—such as sanctions—legally complex and economically risky.

Political Spillover Effects – Leveraging the created assymmetric dependencies

Economic leverage has clear political consequences. In 2017, Greece blocked an EU statement at the UN condemning China’s human rights abuses, breaking what had been a strong European consensus. The move followed major Chinese investments in Greece and was widely interpreted as an example of hybrid pressure at work.

Similar concerns have arisen in Hungary, where Chinese-backed infrastructure projects and educational initiatives (e.g., the attempted establishment of a Fudan University campus in Budapest) have raised questions about political influence and long-term dependency.

Critical Sectors Beyond Ports

Chinese investments extend beyond shipping:

- 5G infrastructure: Chinese telecom firms like Huawei have been involved in the rollout of 5G networks in several EU countries, raising concerns about data security and long-term strategic autonomy.

- Undersea cables and data centers: Ownership or control of digital infrastructure offers potential for information warfare, surveillance, or disruption.

- Critical raw materials: Through strategic investments and partnerships, China exerts influence over supply chains in sectors essential to Europe’s green and digital transitions, including lithium, rare earths, and solar components.

- Renewable energy systems: China’s dominance in solar panel manufacturing has introduced new dependencies, including concerns over so-called „kill switches“ embedded in solar technology. These mechanisms, which could hypothetically allow Chinese manufacturers to disable or degrade systems remotely, raise profound questions about the resilience of European critical infrastructure and energy security in a decarbonizing world.

Conclusion:

China’s hybrid threat posture toward the EU is following a distinct and multifaceted approach, combining traditional strategic culture with innovative uses of modern statecraft. From port acquisitions and economic dependencies to narrative warfare and reflexive digital infrastructure control, Beijing systematically probes and exploits Europe’s vulnerabilities to shape outcomes in its favor.

The EU has taken important steps toward recognizing and addressing this challenge. Instruments like the Anti-Coercion Instrument, improved investment screening, and the Global Gateway are signs of growing strategic maturity. However, these measures remain reactive and fragmented.

To meet the hybrid challenge posed by China, Europe must now move from awareness to anticipation. This requires a more unified and preventive strategic posture—one that fuses internal resilience with external coherence. Applying the Hybrid CoE’s framework consistently across sectors, enhancing public-private cooperation, and reinforcing partnerships with like-minded countries will be key.

Ultimately, safeguarding Europe’s autonomy and democratic integrity in an age of hybrid competition will depend not only on resisting coercion, but also on asserting a compelling strategic vision of its own.

Du muss angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar zu veröffentlichen.